|

Dismissing the use of violence as "both impractical and immoral," Martin Luther King, Jr. (Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968, was an American pastor, activist, humanitarian, and leader in theAfrican-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights using nonviolent civil disobedience based on his Christian beliefs.) endorsed nonviolent resistance as “the only morally and practically sound method open to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.” First introduced to the concept when he read Henry David Thoreau's Essay on Civil Disobedience as a freshman at Morehouse College, King was fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system. While studying at Crozer Theological Seminary, he continued to intellectually explore the philosophy of nonviolence but had doubts about its potential as an instrument for social change. In 1950 King traveled to Philadelphia to hear a talk given by Dr. Mordecai Johnson, president of Howard University. Dr. Johnson had just returned from India and spoke of the life and teachings of Mohandas Gandhi. King was inspired by what he heard, and after reading several books on Gandhi's life and works, his skepticism concerning the power of love and nonviolence diminished. It was the Montgomery bus boycott of 1956, however, that would demonstrate to King the power of nonviolent resistance as a tactical weapon against racial discrimination. With guidance from black pacifist Bayard Rustin, King personally embraced Gandhian principles and chose not to use armed bodyguards despite threats on his life. King recalled, “Living through the actual experience of the protest, nonviolence became more than a method to which I gave intellectual assent; it became a commitment to a way of life. Many issues I had not cleared up intellectually concerning nonviolence were now solved in the sphere of practical action.” The experience in Montgomery enabled King to merge the ideas of Gandhi with Christian theo logy. He recalled, “. . . my mind, consciously or unconsciously, was driven back to the Sermon on the Mount and the Gandhian method of nonviolent resistance. This principle became the guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the sprit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method.” (King would later travel to India to deepen his understanding of Gandhian principles.) In a February 1957 article in Christian Century, King summarized the basis of nonviolent direct action in the struggle for civil rights: 1) This is not a method for cowards; it does resist. The nonviolent resister is just as strongly opposed to the evil against which he protests as is the person who uses violence. His method is passive or nonaggressive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent. But his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade the opponent that he is mistaken. This method is passive physically but strongly active spiritually; it is nonaggressive physically but dynamically aggressive spiritually. 2) Nonviolent resistance does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding. The nonviolent resister must often express his protest through noncooperation or boycotts, but he realizes that noncooperation and boycotts are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation. The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness. 3) This method is that the attack is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who are caught in those forces. It is evil we are seeking to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil. Those of us who struggle against racial injustice must come to see that the basic tension is not between races. As I like to say to the people inMontgomery, Alabama: "The tension in this city is not between white people and Negro people. The tension is at bottom between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. And if there is a victory it will be a victory not merely for 50,000 Negroes, but a victory for justice and the forces of light. We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may happen to be unjust." 4) Nonviolent resistance avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. In struggling for human dignity the oppressed people of the world must not allow themselves to become bitter or indulge in hate campaigns. To retaliate with hate and bitterness would do nothing but intensify the hate in the world. Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can be done only by projecting the ethics of love to the center of our lives. |

A critical study of the life and activities of M.K.Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose. Gandhi is known as father of Nation, Subhas as father of Indian Revolution and Jawaharlal may be said as "a Bridge between the Two".

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Non-Violent as a measure of Freedom Movement

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Entry of Subhas Bose in India politics (contd-1)

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more briefly known as Mont-Ford Reforms were reforms introduced by the British Government in India to introduce self-governing institutions gradually to India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Samuel Montagu, the Secretary of State for India during the later parts of World War I and Lord Chelmsford, Viceroy of India between 1916 and 1921. The reforms were outlined in the Montagu-Chelmsford Report prepared in 1918 and formed the basis of the Government of India Act 1919.)

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more briefly known as Mont-Ford Reforms were reforms introduced by the British Government in India to introduce self-governing institutions gradually to India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Samuel Montagu, the Secretary of State for India during the later parts of World War I and Lord Chelmsford, Viceroy of India between 1916 and 1921. The reforms were outlined in the Montagu-Chelmsford Report prepared in 1918 and formed the basis of the Government of India Act 1919.)The Prince of Wales was due to India to pacify public opinion and to prepare the ground for the inauguration of the constitutional reforms recommended in the Montagu-Chelmsford Report .

But it had a contrary effect at the back ground of Jallianwala Bagh injury. The Congress asked the people to Boycott the Prince's Visit and to observe a hartal on 17th Nov 1921, the day scheduled for the Prince's landing in Bombay.

On 10 Dec 1921, Bose and Das were arrested for parading illegally and received a sentence for six months simple imprisonment. "only six months", Bose mocked at the Magistrate, " have I then stolen a chicken,"

This was the first of the 11 jail terms Bose undergone during the period of his stay in the country.

In prison Bose lived in close proximity with C.R.Das which enriched his political career.

On Dec 12,1921, Janaki Nath Bose wrote to Sarat Bose,

"We are proud of Subhas and proed of you all. I am not at all sorry, as I believe in the doctrine of Sacrifice, in fact, I was expecting it almost daily.Your mother has taken the incident in a bold spirit and thinks that such sacrifices will ultimately lead to Swaraj. Please convey to dear Subhas our heartfelt blessings."

Friday, November 28, 2014

Entry of Subhas Bose in India politics

Subhas had well-formed political opinions even before joining active politics.At Cambridge he studied modern European History including some original source books " These original sources", Bose recalls, " more than anything elseI studied at Cambridge, helped to rouse my political sense and to foster my understanding of the inner currents of International Politics." He followed the path of "uncompromising idealism" to achieve his goal. He had already made up his mind that revolution was needed to to fight imperialism and for this the Indian people had to be organised. He believed that the ideas of revolution were not to be imported either Russia or any other country of the world.

Bose arrived from Cambridge to Bombay on 16 July 1921. when Congress had already taken decision on Non-Violent and Non-Cooperation movement to be adopted to achieve Independence.

As suggested by C.R.Das with whom he had some correspondence before coming to India.

First Meeting with Gandhiji

Almost immediately after landing in Bombay, Subhas went straight to Mani Bhavan to meet Gandhi when Gandhiji's influence in Congress had increased tremendously and Congress had decided in its special session held in Calcutta in the autumn of 1920 to enter a new and dynamic phase with Gandhiji's unique weapons of Satyagraha and Non-Cooperation.

Subhas asked Gandhiji three questions.

1. How were the different activities conducted by the Congress likely to culminate in the last stage of the campaign , viz. the non-payment of taxes ?

2. How could mere non-payment of taxes or civil disobedience force the Government to retire from the field and and leave India a free nation ?

3. How could the Mahatma promise Swaraj within one year as he had been constantly doing ?

his reply to the first question satisfied Bose; that to the second did not appeal to him while the third fared no better.

Bose's initial confrontation with Gandhi thus revealed the gulf between their thinking and approach to political problems.

"Though I tried to persuade myself at the time that there must have been a lack of understanding on my part," Bose wrote later, "my reason told me clearly,again and again,, that there was a deplorable lack of clarity in the plan that the Mahatma had formulated and that he himself did not have a clear idea of the successive stages of the campaign - which would bring India to her cherished goal of freedom."

Bose did not surrender himself to the magic personality of Mahatma, rather he went straight to C.R.Das to report in Calcutta.

C.R.Das and Motilal Nehru were perhaps the only two leadership who could claim to be anywhere near the level of Gandhi. Apart from his legal brilliance and forensic skill , Das had the heart of a poet and the spirit of a revolutionary. His munificence was proverbial.

Bose was captivated by Das at their first meeting ; "During the course of our conversation I began to feel," he recalled later , "that here was a man who knew what he was about and could give all that they could give, a man to whom youthfulness was not a short coming but a virtue. " This time Bose felt that he had found a leader to follow.

Das welcomed him with a number of responsible jobs,

1. He was put in charge of publicity for the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee and made the head of the National Volunteer Corps.

2. He was also appointed Principal of the newly started National College

3.. Editor of Banglar Katha, a nationalist Paper founded by C.R.Das, and then Forward, a English daily, and Atma Shakti

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Entry of Jawaharlal Nehru in Indian Politics

Nehru emerged from the war years as a leader whose political views were considered radical. Although the political discourse had been dominated at this time by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a moderate who said that it was "madness to think of independence", Nehru had spoken "openly of the politics of non-cooperation, of the need of resigning from honorary positions under the government and of not continuing the futile politics of representation."Nehru ridiculed the Indian Civil Service (ICS) for its support of British policies. He noted that someone had once defined the Indian Civil Service, "with which we are unfortunately still afflicted in this country, as neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service." Motilal Nehru, a prominent moderate leader, acknowledged the limits of constitutional agitation, but counselled his son that there was no other "practical alternative" to it. Nehru, however, was not satisfied with the pace of the national movement. He became involved with aggressive nationalists leaders who were demanding Home Rule for Indians.

The influence of the moderates on Congress politics began to wane after Gokhale died in 1915. Anti-moderate leaders such as Annie Beasant and Lokmanya Tilak took the opportunity to call for a national movement for Home Rule. But, in 1915, the proposal was rejected due to the reluctance of the moderates to commit to such a radical course of action. Besant nevertheless formed a league for advocating Home Rule in 1916; and Tilak, on his release from a prison term, had in April 1916 formed his own league. Nehru joined both leagues but worked especially for the former. He remarked later: "[Besant] had a very powerful influence on me in my childhood... even later when I entered political life her influence continued." Another development which brought about a radical change in Indian politics was the espousal of Hindu-Muslim unity with the Lucknow pact at the annual meeting of the Congress in December 1916. The pact had been initiated earlier in the year at Allahabad at a meeting of the All-India Congress Committee which was held at the Nehru residence at Anand Bhawan. Nehru welcomed and encouraged the rapprochement between the two Indian communities.

Home rule movement

Several nationalist leaders banded together in 1916 under the leadership of Annie Besant to voice a demand for self-government, and to obtain the status of aDominion within the British Empire as enjoyed by Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand and Newfoundland at the time. Nehru joined the movement and rose to become secretary of Besant's All India Home Rule League. In June 1917 Besant was arrested and interned by the British government. The Congress and various other Indian organisation threatened to launch protests if she were not set free. The British government was subsequently forced to release Besant and make significant concessions after a period of intense protests.

Non-cooperation

The first big national involvement of Nehru came at the onset of the non-co-operation movement in 1920. He led the movement in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). Nehru was arrested on charges of anti-governmental activities in 1921, and was released a few months later. In the rift that formed within the Congress following the sudden closure of the non-co-operation movement after the Chauri Chaura incident, Nehru remained loyal to Gandhi and did not join the Swaraj Party formed by his father Motilal Nehru and CR Das.

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Satyagraha-1st applied in Champaran in 1817 and Kheda in 1918 by Gandhi

The Kochrab Ashram was the first ashram in India organized by Mohandas Gandhi, the leader of the Indian independence movement, and was gifted to him by his friend Barrister Jivanlal Desai. Founded in May, 1915, Gandhi's Kochrab Ashram was located near the city of Ahmedabad in the state of Gujarat.

This ashram was a major centre for students of Gandhian ideas to practise satyagraha, self-sufficiency, Swadeshi, work for the upliftment of the poor, women, and untouchables, and to promote better public education and sanitation. The ashram was organized on a basis of human equality, self-help, and simplicity. However, as Kochrab became infested with plague after two years, Gandhi had to relocate his ashram, this time to the bank of the Sabarmati River. During his time at theSabarmati Ashram Gandhi's reputation as the voice of the masses and as the leader of the nation would further increase

Gandhiji in

Accompanied by Babu Rajendra Prasad, Mazharul-Huq, J.B. Kripalani, and Mahadev Desai Gandhiji reached Champaran in 1917 Ford conducting a detailed enquiry into the condition of the peasantry. The infuriated district officials ordered him to leave Champaran, but he rejected the order and was willing to face trial and imprisonment. This forced the Government to cancel its earlier order and to appoint a committee of enquiry on which Gandhiji served as a member. Ultimately, the disabilities from which the peasantry was suffering were reduced and Gandhiji had won his first battle of civil disobedience in India.

Ahmedabad Mill Strike : The next scene of Gandhiji's activity was in 1918 at Ahmedabad where an agitation had been going on between the labourers and the owners of a cotton textile mill for an increase of pay. While Gandhiji was negotiating with the millowners, he advised the workers to go on strike and to demand 35% increase in wages. Having advised the strikers to depend upon their conscience, Gandhiji himself went on a "fast unto death" to strengthen the workers resolved to continue the strike. The mill owners gave away and a settlement was reached after 21 days of strike. The millowners agreed to submit the whole issue to a tribunal. The strike was withdrawn and retrieval later awarded the 35% increase that the workers had demanded. Ambalal Sarabhai's sister, Anasuya Behn, was one of the main lieutenants of Gandhiji in this struggle in which her brother and Gandhiji's friend was one of the main advisories.

Kheda Satyagraha: in 1918, Gandhiji learned that the peasants of Kheda district in Gujarat were in extreme distress due to the failure of crops, and that their appeals for the remission of land revenue were being ignored by the government. As the crops were less than one fourth of the normal yield, the peasants were entitled under the revenue code to a total remission of the land revenue. Gandhiji organised Satyagraha and asked the cultivators not to pay land revenue till their demand for remission was met. The struggle was withdrawn, when the government issued instructions that revenue should be recovered only from those peasants who could afford to pay. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was one of the many young persons who became Gandhiji's follower during the Kheda peasant struggle.

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Letter-2 of Subhas Chandra written to Deshabandhu

These letters offer a glimpse into the developing mind of Bose.By these times he studied Bismarck's Autobiography, Mattermich's Memoirs, Mazzini's Writtings, Cavoirs Letters, and Garibaldi's exploits.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Subhas Chandra preferred to serve the country than to serve the British Govt.

Subhas Chandra passed the Tripos and secured fourth position in the ICS examination.But he decided to serve the country instead of serving the British Govt. He was the most brilliant student among all the National Leaders of India. He passed all the University exam. securing creditable position. He wrote in his autobiography, "Indian Pilgrim", " The principal has done justice to me by rusticating me because from that day I discovered my self reliance and my endeavor . I found my capacity of taking the leadership and enjoyment of sufferings to fulfil an ideal." He expressed his desire to Sarat Chandra Bose .

He wrote

to Sarat Chandra Bose in two different letters dated 16 and 23 February of 1921. On 16th Feb. he wrote, " I want to start my career with an ideal of sacrificing for my country. In my imagination I feel much more affinity in sacrificing my life for the country and for living a simple life with an ideal. Moreover, I think that it is a heinous activity of serving under a foreign ruler. The path followed by Aurobindo seems to me of more attractive and great sacrificing, and inspiring, though this path is spread with more thorns than that of the path of Ramesh Datta who passed the ICS Exam and came back to India after being a barrister and became the first district magistrate."

to Sarat Chandra Bose in two different letters dated 16 and 23 February of 1921. On 16th Feb. he wrote, " I want to start my career with an ideal of sacrificing for my country. In my imagination I feel much more affinity in sacrificing my life for the country and for living a simple life with an ideal. Moreover, I think that it is a heinous activity of serving under a foreign ruler. The path followed by Aurobindo seems to me of more attractive and great sacrificing, and inspiring, though this path is spread with more thorns than that of the path of Ramesh Datta who passed the ICS Exam and came back to India after being a barrister and became the first district magistrate.". He mentioned in another letter to Sarat Chandra Bose written on 23rd Feb, " it is only possible for one to sacrifice for the country when he leaves all prosper in earthly life."

He wrote two letters to Deshabandhu Chittaranjan Das on 16.2.1921 (Letter-1, P-1-left, p-2 right)

He wrote two letters to Deshabandhu Chittaranjan Das on 16.2.1921 (Letter-1, P-1-left, p-2 right)

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

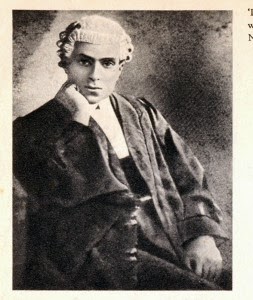

Jawahar Lal Nehru as a legal practitioner

After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru went to London and stayed there for two years for law studies at theInns of Court School of Law (Inner Temple). During this time, he continued to study the scholars of the Fabian Society including Beatrice Webb.[10] Nehru passed his bar examinations in 1912 and was admitted to the English bar.

After returning to India in August 1912, Nehru enrolled himself as an advocate of the Allahabad High Court and tried to settle down as a barrister. But, unlike his father, he had only a desultory interest in his profession and did not relish either the practice of law or the company of lawyers. Nehru wrote: "Decidedly the atmosphere was not intellectually stimulating and a sense of the utter insipidity of life grew upon me. His involvement in nationalist politics would gradually replace his legal practice in the coming years.

The

end of World War II marked a dramatic change. The end of the war was greeted in

India with a vast sigh of relief. However, the issue which most caught the

popular imagination was the fate of the members of Netaji

Subhash Chandra Bose's Indian National Army (INA), who were captured by the British in the eastern theater of the war. An announcement by the Government, limiting trials of the INA personals to those guilty of brutality or active complicity, was due to be made by the end of August 1945. However, before this statement could be issued. Nehru raised the demand for leniency at a meeting in Srinagar on 16th August 1945. The defence of the INA prisoners was taken up by the Congress and Bhulabhai Desai, Tej Bahadur Sapru, K.N. Katju, Nehru and Asaf Ali appeared in court at the historic Red Fort trials. The Congress organized an INA relief and enquiry committee, which provided small sums of money and food to the men on their release, and attempted to secure employment for them.

The INA agitation was a landmark on many counts: Firstly, the high pitch or intensity at which the campaign for the release of INA prisoners was conducted was unprecedented. This was evident from the press coverage and other publicity it got, from the threats of revenge that were publicly made and also fiom the large number of meetings held.

Initially, the appeals in the press were for clemency to 'misguided' men, but by November 1945, when the first Red Fort trials began, there were daily editorials hailing the INA men as the most heroic patriots and criticizing the Government stand. Priority coverage was given to the INA trials and to the INA campaign, eclipsing international news. Pamphlets, the most popular one being 'Patriots Not Traitors,' were widely circulated, 'Jai Hind' and 'Quit India' were scrawled on walls of buildings in Ajmer. Posters threatening death to '20 English dogs for every INA man sentenced', were pasted all over Delhi. In Benaras, it was declared at a public gathering that 'if INA men were not saved, revenge would be taken on European children.' One hundred and sixty political meetings were held in the Central Provinces and Berar alone in the first fortnight of October 1945 where the demand for clemency for INA prisoners was raised. INA Day was observed on 12 November and INA Week from 5 to 11 November 1945. While 50,000 people would turn out for the larger meetings, the largest meeting was the one held in Deshapriya Park Calcutta. Organized by the INA Relief Committee, it was addressed by Sarat Bose, Nehru and Patel. Estimates of attendance ranged from to two to three lakhs to Nehru's five to seven lakhs.

The second significant feature of the INA campaign was its wide geographical reach and the participation of diverse social groups and political parties. This had two aspects. One was the generally extensive nature of the agitation, the other was the spread of pro-INA sentiment to social groups hitherto outside the nationalist pale. The Director of the Intelligence Bureau coceded: 'There has seldom been a matter which has attracted so much Indian public interest, and it is safe to say, sympathy.' Municipal Committees, Indians abroad and Gurudwara Committees subscribed liberally to the INA funds. The Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandhak Committee, Amritsar donated Rs. 7,000 and set aide another Rs. 10,000 for relief. Diwali was not celebrated in some areas of Punjab in sympathy with the INA men. Calcutta Gurudwaras became the campaign center for the INA cause. The Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu Mahasabha and the Sikh League supported the INA cause..

Subhash Chandra Bose's Indian National Army (INA), who were captured by the British in the eastern theater of the war. An announcement by the Government, limiting trials of the INA personals to those guilty of brutality or active complicity, was due to be made by the end of August 1945. However, before this statement could be issued. Nehru raised the demand for leniency at a meeting in Srinagar on 16th August 1945. The defence of the INA prisoners was taken up by the Congress and Bhulabhai Desai, Tej Bahadur Sapru, K.N. Katju, Nehru and Asaf Ali appeared in court at the historic Red Fort trials. The Congress organized an INA relief and enquiry committee, which provided small sums of money and food to the men on their release, and attempted to secure employment for them.

The INA agitation was a landmark on many counts: Firstly, the high pitch or intensity at which the campaign for the release of INA prisoners was conducted was unprecedented. This was evident from the press coverage and other publicity it got, from the threats of revenge that were publicly made and also fiom the large number of meetings held.

Initially, the appeals in the press were for clemency to 'misguided' men, but by November 1945, when the first Red Fort trials began, there were daily editorials hailing the INA men as the most heroic patriots and criticizing the Government stand. Priority coverage was given to the INA trials and to the INA campaign, eclipsing international news. Pamphlets, the most popular one being 'Patriots Not Traitors,' were widely circulated, 'Jai Hind' and 'Quit India' were scrawled on walls of buildings in Ajmer. Posters threatening death to '20 English dogs for every INA man sentenced', were pasted all over Delhi. In Benaras, it was declared at a public gathering that 'if INA men were not saved, revenge would be taken on European children.' One hundred and sixty political meetings were held in the Central Provinces and Berar alone in the first fortnight of October 1945 where the demand for clemency for INA prisoners was raised. INA Day was observed on 12 November and INA Week from 5 to 11 November 1945. While 50,000 people would turn out for the larger meetings, the largest meeting was the one held in Deshapriya Park Calcutta. Organized by the INA Relief Committee, it was addressed by Sarat Bose, Nehru and Patel. Estimates of attendance ranged from to two to three lakhs to Nehru's five to seven lakhs.

The second significant feature of the INA campaign was its wide geographical reach and the participation of diverse social groups and political parties. This had two aspects. One was the generally extensive nature of the agitation, the other was the spread of pro-INA sentiment to social groups hitherto outside the nationalist pale. The Director of the Intelligence Bureau coceded: 'There has seldom been a matter which has attracted so much Indian public interest, and it is safe to say, sympathy.' Municipal Committees, Indians abroad and Gurudwara Committees subscribed liberally to the INA funds. The Shiromani Gurudwara Prabhandhak Committee, Amritsar donated Rs. 7,000 and set aide another Rs. 10,000 for relief. Diwali was not celebrated in some areas of Punjab in sympathy with the INA men. Calcutta Gurudwaras became the campaign center for the INA cause. The Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu Mahasabha and the Sikh League supported the INA cause..

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)